The occasion of both a major exhibition in a public museum and the publication of a monograph devoted to him is cause enough for a re- assessment of the career and achievements of Edward Ardizzone (1900- 79). The exhibition, at the House of Illustration in London’s booming King’s Cross quarter, ran from September to January, and was the first major retrospective in forty years. Why such a long gap since the last? Ardizzone is perennially popular, but paradoxically this doesn’t mean that museums will readily show him. What I call the Lowry factor is at work here: if the art is widely enjoyed it is automatically suspect to curators. For when the public is intimately familiar with an artist, what is left for the curator to do? Unless to identify him as a Marxist, as the recent Tate show of Lowry farcically attempted.

The exception to this rule is David Hockney, in a category of museum stardom all of his own, but his work is so full of intellectual theories and gimmicks that he is a contemporary curator’s dream – witness the enthusiastic capitulation of the Royal Academy (twice), the National Portrait Gallery and now the Tate to the power of Hockney box office. For his part, Ardizzone has been deeply loved by generations of children and adults, and Alan Powers, in his book Edward Ardizzone: Artist and Illustrator, seeks to establish why. This handsome hardback monograph, lavishly illustrated and clearly and concisely written, is a splendid tribute and fitting accompaniment to the House of Illustration’s exhibition (which Powers helped to organise). Elegantly produced, it makes a prodigious pair with Powers’ recent bestselling book on Eric Ravilious, also published by Lund Humphries.

Ardizzone grew up in Suffolk, in Constable’s birth-place of East Bergholt, and was later sent to the grammar school in Ipswich. In his utterly delightful memoir, The Young Ardizzone (published in 1970), he wrote:

Ipswich in 1910 was a rough, tough town. One did not venture into the populous parts on a Saturday night because of the drunks who were often found lying insensible in the gutter…. Even in the daytime one could, in the poorer areas of the town, see much drunkenness. I, as a small boy, was privileged to witness a magnificent example of this.

He then went on to describe a street fight outside a public house between two women, watched through the window by the men in the public bar:

They fought each other clawing, scratching and shrieking like tiger cats. Both had long, raven-black hair which tumbled down over their backs and shoulders. Both wore nothing but a thin white nightdress and both were bare-footed as if they had just got out of bed. At one moment the stouter of the two dragged her opponent along the pavement by the hair. The next moment the thin one retaliated by tearing away the front of the other’s nightgown, leaving her heavy breasts and most of her belly exposed.

As can be deduced from the vividness of the description, the incident was blazoned upon the young Ardizzone’s memory, not least for the fact that no one attempted to interfere. He commented:

This scene has always haunted me and many times in years since I have tried to draw it from memory and put down on paper the wild movement of the fighting women in the still setting of the street. I am sure it was a formative moment in my career as an artist.

Although he disliked Ipswich, and was never really happy there, his visits to the docks with an intrepid friend formed the first inspiration for his Little Tim books which were to be such an important cornerstone of his subsequent popularity.

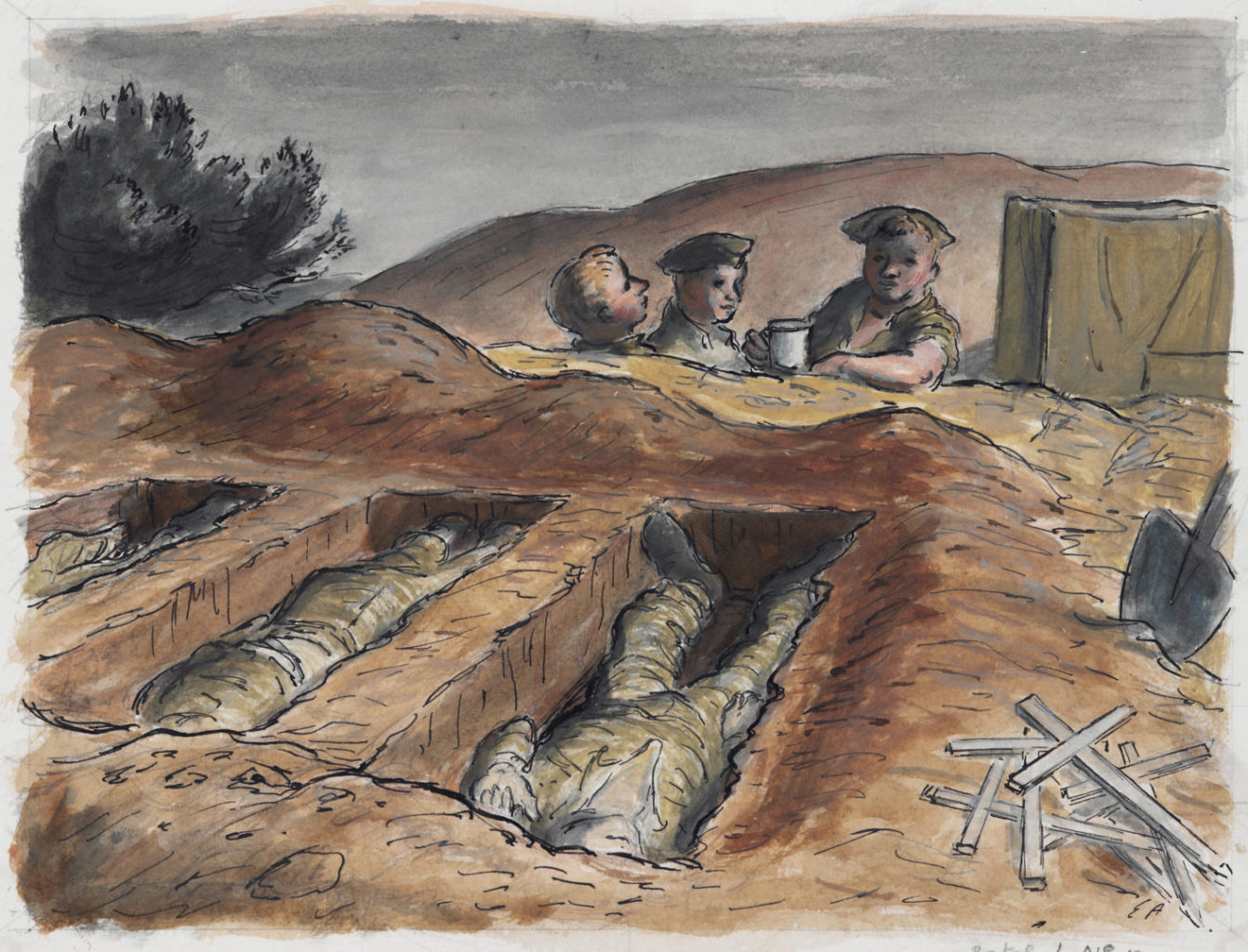

Alan Powers argues that relatively few artists have defined illustration for their generation. He cites Quentin Blake today and Beatrix Potter for the earlier twentieth century, and writes that ‘nobody else qualifies to be their equivalent during the intervening time period as [Ardizzone] does’. His greatest fame is as an author and illustrator for children, but one thing the exhibition made clear was just how good a painter he was. This can be most easily seen in the work he made during his years as an official War Artist (1940-45), particularly in a couple of large watercolours which were hanging in the second room of the show: A Drunken Dutchman in a Street in Bremen and A Battery Position in an Orchard of Young Fruit Trees in the Snow, both of 1945. (Could the latter possibly be a slant reference to that famous 1883 spoof on abstraction by Alphonse Allais entitled First Communion of Anaemic Virgins in the Snow?)

Ardizzone cared little for Modernism and even less for fashion. Undoubtedly, much of the enduring strength of his work derives from his independent vision, and his ability to bring tenderness, sensuality and humour to his work in equally potent measures. Certainly the subtlety of his watercolour works effectively with the graphic drive of his ink line, and although he seldom had recourse to oil paint, he could also make a telling image on canvas – witness his 1935 painting Men in a Pub, a lifelong favourite subject ably captured.

Both monograph and exhibition made me want to ferret out books illustrated by Ardizzone I’d enjoyed as a child: Stig of the Dump by Clive King, The Otterbury Incident by C Day Lewis, de la Mare’s Peacock Pie; and more recently, H.E. Bates’s marvellous My Uncle Silas. The spirited cross-hatching, the dextrous scribbliness, the tonal nuance are both witty and immensely evocative, proof of Ardizzone’s ability to inhabit a story. He dealt in types and archetypes which exist in an eternal present and are not above ironic self-satire. There’s a refreshing lack of preciousness to his work, an anarchic temper within a classical design of economy and simplicity, an earthiness in the wonderfully non-judgmental record of reality. His genuine feeling for landscape tends to be played down, but his sympathy for the shabbier end of society is ever-present. Born in Algeria of an Italian father and half-Scots mother, he was in some ways more European than English. Although Kenneth Clark placed him in the tradition of the English Grotesque, along with Rowlandson, Cruikshank and Leech, perhaps his closest artistic relation was Daumier, who also managed to combine the roles of artist and illustrator. Looked at afresh today, Ardizzone re-emerges as a great individualist whose generous spirit continues to nourish us.

Andrew Lambirth is a writer about art who also writes poetry and makes collages. Besides contributing to a range of publications including The Sunday Telegraph, The Guardian and RA Magazine, he was art critic for The Spectator from 2002 until 2014, and has collected his re- views in a paperback entitled A is a Critic. Among his recent books are monographs on the artists David Inshaw, Eileen Gray and William Gear. He lives in Suffolk surrounded by pictures.

You must be logged in to post a comment.